I took my son, Cam, to his first jiu-jitsu class last week.

We met his coach, and just like that, I gave my little dude the nod to get out onto the mat.

He ran off, sheepishly though, until it turned into a walk veering away from the kids who’d already lined up. The coach gently nudged him on track.

Warm-ups commenced. He was the last to finish each movement, a younger boy—probably the coach's son—stayed by him, guiding him through. They did forward and back rolls. Cam would lean into the movement but come to a complete stop, like he forgot how to make his body move, leaving his shoulder planted in the mat. During backward rolls, he looked like a squashed slug stuck upside down, struggling against gravity. To keep class moving, the helper had him run back halfway.

During instruction, the coach asked the kids to name the positions they learned last week. Cam’s hand shot up each time, his eyes bright with the same eagerness as the other kids—even though he didn’t know a single answer. He just wanted to be part of it.

Then came time to “roll” with his partner. The image of a slippery fish comes to mind—he ran around in circles most of the time, karate chopping the air or dazing off into open space.

He’d look over at me between rolls, his face a mix of “holy shit” and excitement, and I’d nod, “Nice job, buddy.” But under the surface, I was torn. Every stumble, every uncoordinated movement had me cringing—not because of him, but because I felt the eyes of other parents, imagined their judgment, as if his movements were somehow reflecting on me. I wondered, did they see the kid trying his hardest, or just a dad whose son wasn’t quite hitting the mark?

Near the end of class, the studio’s owner—a 6’ jacked dude with a purple belt and a distinct army green Gi—was watching over him. Suddenly, I felt the full intensity of my own thoughts, the pressure in my chest.

Fear crept in: that my boy wasn’t “tough,” that he might be seen as “spacey.” I told myself to relax. He’s barely six. It’s his first time. Give him a break.

Yet, I couldn’t shake the unease. My mind was racing with judgments. A part of me wanted him to excel, but a bigger part wanted to protect him from looking “weak.” I found myself mentally pushing him: C’mon, get in there. Push, don’t let go. Let’s go—you got this. It was demanding, relentless. Figure it out. Now.

I wondered if my dad had felt the same way watching me. When I was a kid, his relentless drive to “toughen me up” shaped every sport we did together. I became good—often the best. I’d wake at 5 a.m. to run before school, lifted weights daily, and he even had me wearing ankle weights in fourth grade to “get faster.” His push turned into my discipline, but it came with a price: tension, friction, and the constant feeling I could never do enough. I never had a choice.

So as my son’s class ended, I was confused about what he needed from me. I wondered, do I need to be pushing him more?

Wait a second, I thought, is there even a problem here? Maybe the only issue is me–and my stuff. My judgements were stealing his innocence. This class had triggered a flood of memories with my dad, his relentless expectations, and my own sense of not being enough.

And that’s when it hit me—was this class about skill and performance, or something else? I’d become fixated on the former. Wasn’t he here to stumble, to feel that awkwardness, to get back up and learn that it’s okay not to be perfect? This is beginning. I realized I needed to check my own ego at the door if I wanted him to feel free to try, to fail, to just be. To have fun.

There was a deeper tension too: I wanted my son to be resilient and capable, but without falling back on the rigid discipline I’d been handed down. How much is too much? When does guidance become pressure? I wanted him to find his own strength, but I wrestled with when—and how much—to step back.

I recently started reading Empire of the Summer Moon by S.C. Gwynne, where young Comanche boys were trained rigorously to become warriors. They learned to endure pain, master horsemanship, and show no fear—lessons vital for survival in a dangerous world. And it got me thinking: how do I nurture a similar resilience today?

He’s not training for battle, but I still want him ready for life’s challenges, strong and self-reliant—without the harshness those boys faced. Or, you know, without me turning into some crazy dad. And if you’re thinking, “chill, dude”—I get it. This is coming from the guy who runs through the woods listening to The Last of the Mohicans on repeat. (here’s the entire track, Promentory if you’re up for a wild run)

I couldn’t really articulate this experience to my wife that evening. I could just share some sense that jiu-jitsu seems really good for him, that he needs this and some sense of it stirring up something deep inside me around my own relationship with my father. I want to be a champion for Cam, involved in his growth, but with love and connection instead of force and pressure. I want him to have a choice. I want him to have fun.

The next morning, I sat at the kitchen counter, eating yogurt with one hand and holding our baby with the other. She nuzzled into me, tickling the back of my head with her tiny hand. My wife grabbed her camera, wanting to capture the moment.

It must have seemed precious... but here I was, wrestling with the push and pull of fatherhood, wondering how to raise my son into a fierce AND loving warrior ready for the world—without inflicting unnecessary pain or risking our connection.

I was aware of the preciousness of this moment yet unable to fully be in it. I know this feeling.

Moments later, my wife took the baby to put her down for a nap. I kept staring into space, with the ruckus of my other three kids playing just behind me.

This feeling is like a slow, dull wave of pain washing over me until I’m paralyzed—until all I can do is sit there, tears welling in my eyes like a glass overflowing under a running faucet. And in that stillness, I can hear an echo of my dad’s voice: Quit crying. You want to get better, don’t you?

Constructive criticism, he’d call it.

I remember being on my childhood little league field, my dad tossing me ball after ball. Just the two of us, father and son, coach and player always merging. I swing and miss. Then again. Swing and miss, swing and miss, swing and miss. Ahhh, I start grunting, huffing and puffing each time I miss. “Keep your back elbow up, let’s go.” “You dropped it again.” “Calm down, just listen to me.” I get more heated, I’m crying and kind of unravel but he’s relentless. “You’re gonna hit this goddam ball, if you’d just listen to me.” Each miss only heightened his intensity, until all I wanted was for it to stop.

This is how it usually went, building and building until one of us finally erupted, bringing it all to an end. Just one of hundreds of moments like this to choose from.

As I watched Cam’s first class end, I realized I want things to be different for us. Yes, I think jiu-jitsu would be fun and valuable for him. But he’s only five—he doesn’t need to be anything other than who he is—a boy learning about the world. I’m learning it’s on me to loosen my grip, to let him learn at his own pace, not excel at everything, and sometimes, to dislike what I love. I want him to explore, struggle, and grow because he chooses it, not because I push him. I’m learning that sometimes, my work as a father is to release the need to shape him and instead be present in his unfolding. I hated martial arts as a kid; my dad made me stick with karate for seven years. “You don’t quit” was his eternal mantra.

I commit. I follow through. I get things done. I’m good at that. The Marines reinforced it: mission accomplishment above all. But perhaps I’m already passing these qualities onto my son, by bringing him to class and simply being there to support him.

I didn’t quit. Not once—until I started quitting jobs after the Marines. And suddenly, it was freeing. Wait, this doesn’t feel right… I don’t have to stay? I can choose a different path and trust my own process? Imagine if I’d spent 30 years in tech sales, just toughing my way through it, all because that old programming kept me from seeing any other path.

On the outside, I look like a man with success—an amazing wife, a father of four, a six-figure coach, honing new creative practices, physically fit. Yet the old belief of “not being enough” still creeps in, always stealthy in nature blinding me to who I am. My dad’s methods “worked” for me, but I don’t want my son to carry these silent weights.

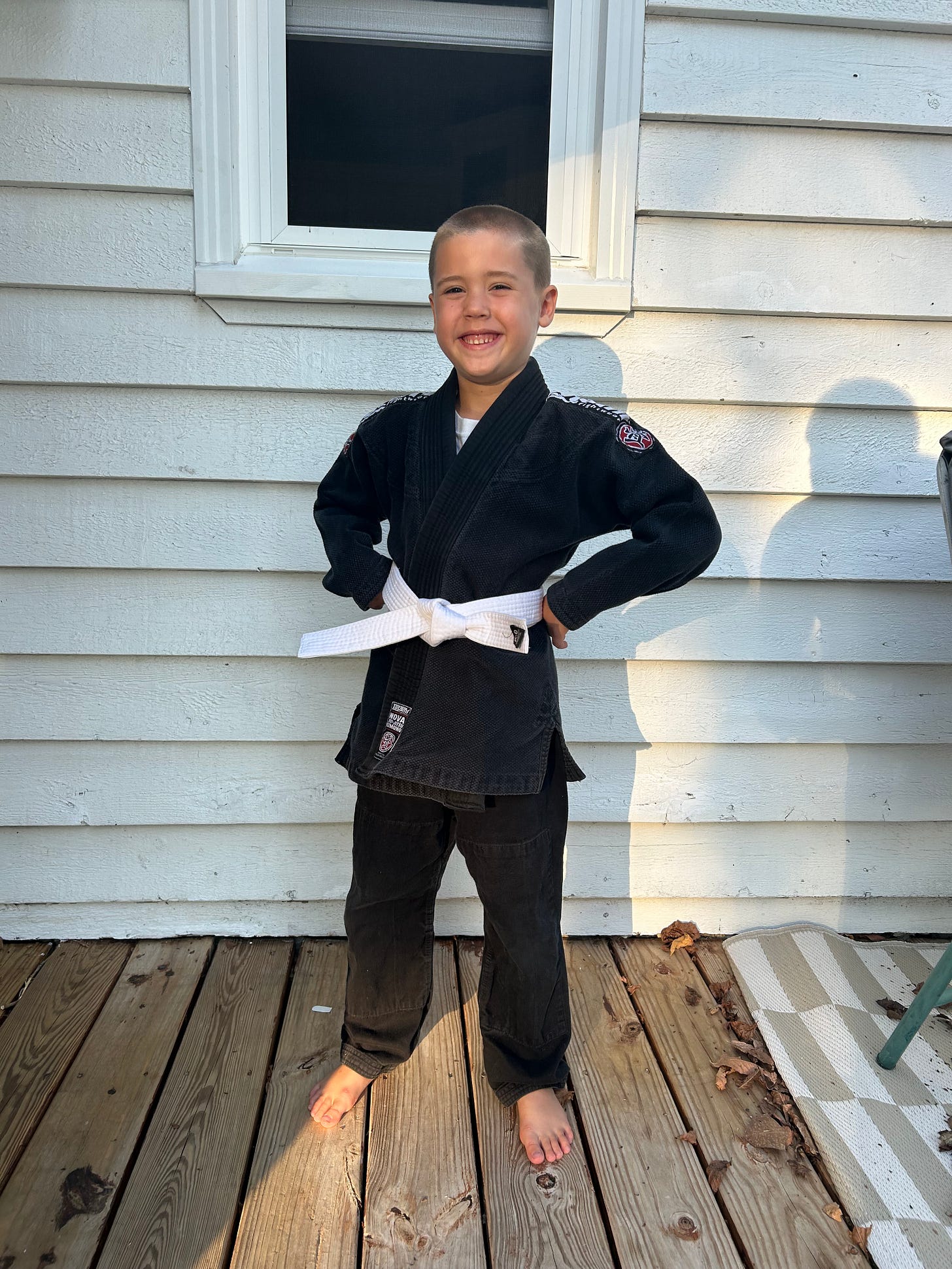

My son is where he’s supposed to be, moving at his own pace. Right now, my role is to love, accept, and support him on his way. Look at that photo, it reveals the truth — his pure goodness. That’s where I am meant to attune.

Every time I think I’ve healed, life reveals deeper layers. This was another opening to an old wound—a reminder of what I needed as a boy and a question of whether I can give my son what he truly needs.

"Every stumble, every uncoordinated movement had me cringing—not because of him, but because I felt the eyes of other parents, imagined their judgment, as if his movements were somehow reflecting on me." This is so honest and true as a parent. Loved the perspective you offer here, and the internal tension you share with us. Really made me reflect, thanks for sharing!

Great essay. Nothing wrong with a trail run with Natty Bumppo. Love the awareness of this. So hard (and ironic) to know if, as a parent, the magnitude of improvement vs how we were raised is enough for our own children. Imo, it’s one of the most challenging things to know as a parent, how much is enough. This piece captured that very well. It is an ongoing grapple. Keep bringing the goods 👊